Our bodies need water to transport oxygen, lubricate joints, keep skin supple, regulate body temperature, detoxify and more. Of course, in order to effectively support detoxification, water needs to be . . . well, non-toxic.

Unfortunately, it’s been nearly 20 years since the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency has added any contaminants to the list of chemicals regulated under the Safe Water Drinking Act, and that means a whole lot of pollutants are legally allowed to flow into our homes and our drinking glasses.

For example, right now 99% of Americans – including newborn babies – already have a chemical called PFAS in their blood, and more than 200 million of us are likely drinking PFAS polluted water. (1)

That’s a problem, because the EPA recently released this health advisory, which warms that PFAS chemicals are far more toxic than they originally thought, even at “near zero” levels. Or as Erik Olsen of the National Resources Defense Council (NRDC) put it:

The science is clear. These chemicals are shockingly toxic at extremely low doses” (2)

While the EPA has issued new “acceptable level” guidelines for two common PFAS chemicals – PFOA and PFOS – their recommendations are nothing more than suggestions. Water treatment facilities are not legally required to test for, much less remove, PFAS from our drinking water.

So what are polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), how did they end up in both private and public water supplies across all 50 states, and why are they so “shockingly toxic”?

We’ll dive into all that below, plus how to significantly reduce your family’s exposure.

What is PFAS?

PFAS was accidentally discovered in the 1930s by a DuPont chemist named Roy Plunkett. While researching refrigerants like freon, he developed a heat resistant coating called polytetrafluoroethylene that repelled oil, food, dirt, moisture and more.

Known as teflon, polytetrafluoroethylene was the first PFAS chemical ever created, but it wasn’t the last. Today, there are over 9,000 chemicals in the PFAS family, including 600 that are widely used in military and consumer products. (3)

Unfortunately, the nickname “forever chemicals” is no exaggeration for this class of synthetic compounds. Bacteria can’t eat them, which means they don’t break down in the environment. Instead, they leach into soil and contaminate groundwater.

In recent years, as more information has become available about their health risks, companies have replaced older generation PFAS chemicals like PFOA, PFOS, and PFNA with newer ones – particularly GenX and PFBS. Unfortunately, they’re toxic, too. (4)

“Ticking Time Bomb” According To Lead Researcher

According to Bo Guo, the lead researcher in this study on how PFAS contamination spreads through the environment, “They basically fulfill the characteristics of a ticking time bomb.” (5)

That’s because when industrial sites, landfills, airports, and military bases become contaminated with PFAS, the chemicals don’t just stay in the soil. Instead, they work their way into surface water (like rivers) and underwater aquifers that serve as drinking water.

In other words, the levels of PFAS we’re seeing in our water supply will continue to rise, which is a problem because they’re known to bioaccumulate fish, wildlife, and . . . well, us. (6)

Current research suggests that PFAS exposure is linked to a wide range of adverse health effects, including:

- An increased risk of certain cancers (Including kidney, prostate and testicular cancer. Others such as breast cancer may also be linked.)

- Weakened immune system function (7)

- Liver damage (8)

- Elevated cholesterol levels

- Increased risk of asthma (8)

- Fertility problems (9)

For mothers and babies, exposure also increases the risk of:

- Hypertension during pregnancy (10)

- Lower birth weight (7)

- Gestational diabetes (11)

- Childhood obesity, preeclampsia (11)

- Fetal growth restriction (11)

- Variations in bone development (6)

The health risks increase as PFAS accumulates in our bodies, which is why the EPA considered lifetime exposure when they created the new safety recommendations. For two of the most common PFAS chemicals, the previous recommended target of 70 parts per trillion was reduced to just four parts per quadrillion for PFOA and .02 parts per trillion for PFOS.

Common Sources of PFAS Exposure

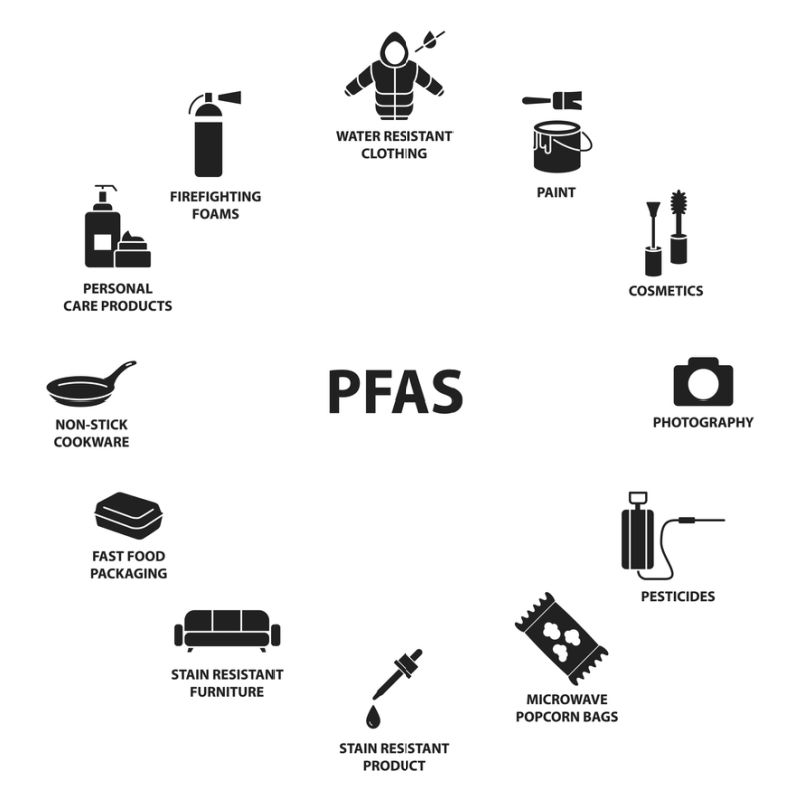

PFAS is commonly found in military, industrial and consumer products, including:

- Drinking water (This is one of the primary routes of exposure, but certain water filters can remove it. More below.)

- Food packaging such as “grease-resistant paper, fast food containers/wrappers, microwave popcorn bags, pizza boxes, and candy wrappers” (12)

- Non-stick cookware

- Conventional cleaning products

- Personal care products including, shampoo, lotions, cleansers, nail polish, shaving cream, and dental floss (13)

- Cosmetics including foundation, lipstick, eyeliner, eyeshadow, and mascara (13)

- Stain resistant carpet, upholstery and other fabrics (12)

- Household dust

- Water repellent clothing, sleeping bags, etc.

- Paints, varnishes and sealants (12)

- Firefighting foam

- Pesticides

- Fresh water fish and/or seafood harvested near highly contaminated sites (For example, DuPont dumped 800 tons of PFOA into the Ohio River, and leaked internal documents show they knew it was toxic.) (14)

How To Reduce PFAS Exposure

- Buy a good water filter (More on that below)

- Ditch non-stick cookware containing PFAS and use stainless steel, cast iron and glass options instead (I’m working on a guide for you)

- Use non-toxic cleaning products

- Change your HVAC filter and dust/mop regularly to remove any PFAS particles present in dust (A good HEPA air filter helps, too.)

- Avoid stain-resistant furniture, carpet, bedding, etc.

- For clothing, look for high-quality materials like organic cotton, OEKO-TEX® Standard 100 fabrics, or GOTS certified fabrics when possible

- Choose non-toxic makeup and personal care products

- Skip takeout containers by cooking at home. Use leakproof glass containers and reusable storage bags to store leftovers when possible.

- Check your local fish advisories before eating locally-caught fish or seafood

What is being done to reduce PFAS in water supplies across the country?

Some states have set their own enforceable limits for PFAS in public water supplies, and a few have even sued PFAS manufacturers for contaminating natural resources. (15) On a nationwide level, the EPA has said that it hopes to set enforceable limits for PFAS by the end of 2023.

While that’s great news, we don’t know yet if the new standards will be strong enough to offer meaningful protection.

Also, most public water systems don’t have the equipment to test for or remove PFAS, and purchasing the equipment may not be economically possible for some communities . . . and least not right away. It’s not clear how long the EPA might give them to become compliant. Will it be months? Years?

In the meantime, PFAS has already been detected in both private and public water supplies across all 50 states, and there’s a lot more in our environment that’s migrating toward our water supply. This is not a contamination problem that can be solved overnight, so I’m taking proactive steps to reduce my family’s exposure while municipalities try to catch up.

Is there PFAS in your water?

Since testing is not required it can be challenging to know whether your local supply is affected. If you have a local public supply, here are a few ways to find out:

- Enter your zip code into this “What’s In Your Water” tool to see if your public water system has proactively chosen to do any PFAS testing

- Use a test kit like this one or this one to measure levels of common PFAS contaminants This is also a good option if you have well water. However, it’s important to remember that although a test might reveal no PFAS today, the water supply is ever changing and today’s results might not match tomorrow’s water.

Water Filters That Remove PFAS

If your public water system doesn’t monitor PFAS and you’d prefer avoid the expense of water testing, another option is to simply choose a water filter that removes PFAS along with other unwanted contaminants like fluoride, lead, pesticides, herbicides, microplastics, and pharmaceuticals.

I’ve written several water filter purchasing guides, including this one for under-sink filters, this one for countertop filters, and this one for whole house filters. Many of them have been tested to remove the two most common forms of PFAS (PFOA and PFOA), and I include that info when it’s available.

My top recommendation is Clearly Filtered, which is what I personally use. It removes more contaminants than the other filtration options I considered – including PFAS – while leaving beneficial minerals intact.

Their pitcher filter, which I use when I travel, is the only pitcher filter certified by the Water Quality Association to remove PFOA/PFOS from drinking water. Additional independent testing shows that it also removes other forms including GenX and PFHA.

Their under sink filter is also rated to remove PFOA and PFOS, plus other forms like PFNA and PFBS. When I asked why it’s not also rated to remove GenX, they explained that they use ten times more water (2,000 gallons) to test the under sink system than is needed for the pitcher, and that at that volume certain forms of PFAS were not available from the testing facility when performance analysis was run.

The two filters use the exact same filtration technology, so I asked if there are any differences between how they function that might cause one to remove a contaminant and the other to let it through. For example, high flow rates reduce the contact time between water and filtration materials, which can reduce the removal rate of certain contaminants.

According to Clearly Filtered, there is no functional difference in performance between the flow rate of the pitcher and under sink system, so even though right now only the pitcher is rated to remove GenX, I think that future testing will show the same results for the under sink system.

Either way, both systems are rated to remove more forms of PFAS than most filters that focus solely on PFOA/PFOS, and they also remove a bunch of other stuff like:

❌ Fluoride

❌ Lead

❌ Chlorine

❌ Pesticides

❌ Herbicides

❌ Microplastics

❌ Phthalates

❌ Pharmaceuticals

If you want to try them out, click here and use code MP15 to save 15%.

Do you have a question about PFAS? Let me know in the comments below!

Related Articles

Want a FREE ebook of non-toxic cleaning recipes that WORK?

I’ve created a free ebook for you as a gift for signing up for my newsletter. 7 Non-Toxic Cleaning Recipes That Really Work covers seven recipes that you can make in just a few minutes each for squeaky clean windows, sparkling dinnerware, lemon-fresh countertops, and more. Subscribe to my newsletter below and you’ll be redirected to a download page for immediate access to this PDF ebook.

Sources

- Environmental Working Group. What Are PFAS Chemicals?

- National Resources Defense Council (2022) EPA Adopts Sharply-Reduced Health Advisories for Key PFAS Chemicals in Drinking Water

- Scientific American (2021) Forever Chemicals Are Widespread in U.S. Drinking Water

- National Resources Defense Council (2018) EPA Finds Replacements for Toxic “Teflon” Chemicals Toxic

- ABC News (2021) ‘Ticking time bomb’: PFAS chemicals in drinking water alarm scientists over health risks

- Environmental Protection Agency. Our Current Understanding of the Human Health and Environmental Risks of PFAS

- Suzanne E. Fenton et. al. (2020) Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substance Toxicity and Human Health Review: Current State of Knowledge and Strategies for Informing Future Research

- Harvard School of Public Health (2018) Health risks of widely used chemicals may be underestimated

- Young Ran Kim et. al. (2020) Per- and poly-fluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) in follicular fluid from women experiencing infertility in Australia

- C8 Science Panel

- John T. Szilagyi et. al. (2020) Perfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) and their effects on the placenta, pregnancy and child development: A potential mechanistic role for placental peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs)

- Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) and Your Health

- U.S. Food & Drug Administration. Per and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) in Cosmetics

- Sarah Brookbank (2017) UC study: Chemical found in Tristate residents likely due to industrial discharge

- Safer States. PFAS